Persian New Year, or Nowruz, explained

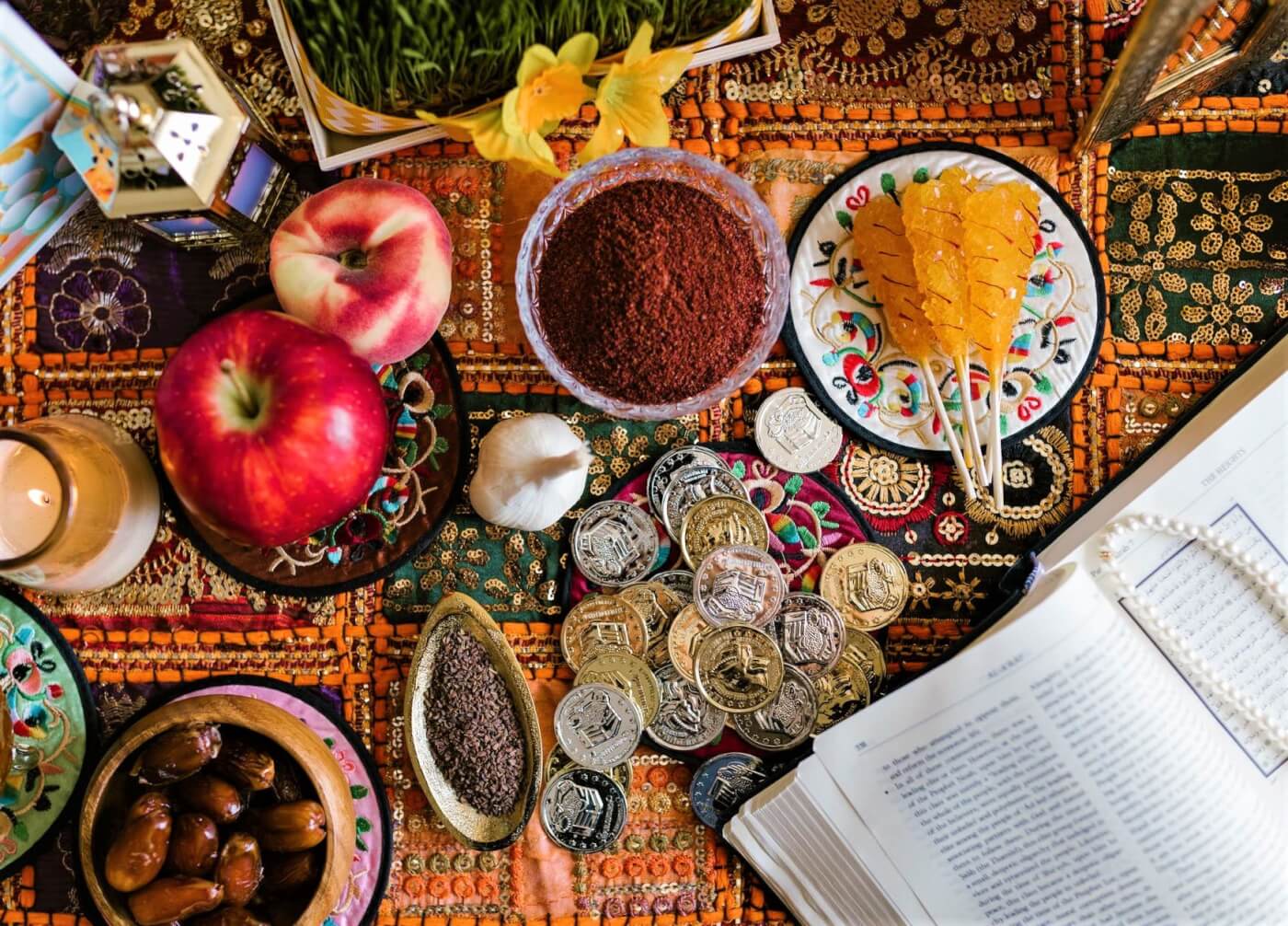

The festival of Nowruz, which takes place on the day of the vernal equinox, celebrates the end of the previous year and the start of the new one.

The concept of “spring cleaning” has been the foundation of a national holiday in Iran for millennia; it’s not just a time of year to declutter your wardrobe.

Many people celebrate Nowruz, also known as the Persian New Year (pronounced “no-rooz”). In Iran, the new year begins with the arrival of spring, and nearly everyone observes it by deep cleaning their homes, celebrating a season of new life, and wishing for luck in the coming year. This is in addition to the millions of Iranians and non-Iranians who celebrate the holiday elsewhere in the world.

Perhaps you’ve heard a little bit about Nowruz. Since 2009, President Obama has sent Nowruz greetings to observers, and in 2010, the United Nations formally declared it a worldwide holiday (although they often doubled as statements on the relationship between the United States and Iran). Even the Obama family’s own haft-seen were present at the White House’s 2015 Persian New Year party, which was hosted by the first lady at the time, Michelle Obama (more on what a haft-seen is later).

However, if you didn’t grow up celebrating Nowruz like I did, the idea can be unclear. In fact, it was a little unclear for me as my first memories of the Persian New Year revolved mainly around drooling over the mouthwatering rice dish my mother would prepare in its honor.

Though, to be fair, food plays a significant role in the majority of holidays celebrated on this globe, after I started to understand more about what Nowruz signifies outside of food, I realized how fascinating its rich customs actually are.

What is Nowruz?

On the day of the vernal equinox, Nowruz celebrates the end of the previous year and the start of the new one.

Rather of starting at the stroke of midnight, the new year actually starts the second the equinox does. The equinox typically occurs between March 19 and March 21; this year, Nowruz falls on the evening of March 20. (However, if you’re an Iranian expat, the equinox occurs at noon Eastern.) However, there are several characteristics of Nowruz that continue to influence Persian society for several weeks after the occasion.

No one is certain of the precise origins of Nowruz. The most accurate predictions fall within a range of 3,000 years. But the most crucial fact about Nowruz’s history is that it has its roots in Zoroastrianism, a pre-Christian and pre-Islamic religion practiced in ancient Persia. (Since Zoroastrianism has a long history and is not limited to Iran or the several Persian Empires that have existed, Nowruz is also observed by millions of people who are not Iranian around the world.)

The new administration attempted to reduce the degree to which Nowruz is observed after the 1979 revolution, citing the holiday’s pre-Islamic origins as justification for its abolition. But even in a country that was deeply divided to the point of uprising, the idea of losing Nowruz sparked a fierce backlash that was too strong to ignore.

After millennia of development, Nowruz is still too cherished, all-encompassing, and ingrained in Persian society to be disregarded.

How do you prepare for Persian New Year?

Additionally, there are many of customs that are tied to the festival because it has been celebrated for so long. However, there are a few fundamental principles that almost everyone who celebrates Nowruz adheres to, whether in Iran and beyond.

A little over three weeks before the real vernal equinox, people begin to prepare for Nowruz. Almost everyone gets serious about spring cleaning, clearing their houses of any extraneous items and lingering filth that has accumulated over the previous year so they can start again. Many Persian rugs are probably hanging outside in Iran at this time of year so that their owners can beat the dust off of them.

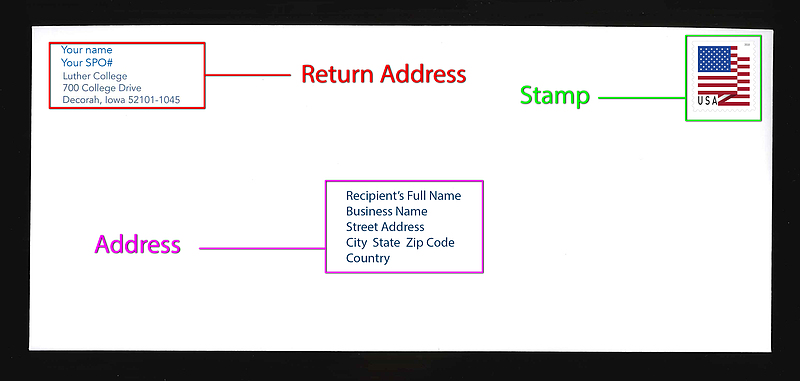

Families also set aside a spot for a “haft-seen,” or a collection of objects that represent a different hope for the new year, during these same weeks preceding the actual day. There are seven elements that are always included in the haft-seen, despite the fact that some families add their own modifications (more on those in a moment):

- Sabzeh: For rebirth and regeneration, some form of sprout or grass that will continue to develop in the weeks before the holiday.

- Senjed: For affection, a dried fruit, preferably a sweet fruit from a lotus tree.

- Sib: Apples promote both health and attractiveness.

- Garlic is a useful food and medication, according to the seer.

- A sweet pudding for prosperity and fertility, samanui

- Vinegar, Serkeh, for the endurance and experience that come with age

- Sumac: A Persian spice used to celebrate the dawn of a new day that is made from crushed tart red berries.

A haft-seen, which literally translates to “seven S’s,” is built on these seven S objects, but the custom has developed to the point where there are various additional items you can add. My family’s haft-seens, for instance, always featured a mirror to represent reflection, colored eggs to represent fertility, coins to represent success, and, if we were feeling adventurous, a live goldfish to represent fresh life (an ironic association in my house, where pretty much every goldfish we brought home died immediately).

The haft-seen is yours to alter once the seven cornerstones have been established. Occasionally, Muslim families will have a Quran. A collection of poetry by Hafez, one of Iran’s most well-known poets, occasionally occupies a place of respect.

Once Nowruz day comes, a 13-day festival that includes meals, family visits, and predictions for the coming year begins. To release the past and welcome the new, on the thirteenth day, you take the sabzeh that has been growing in the haft-seen to any natural body of flowing water you can find and let it float away.

My mother, who was born and raised in Tehran, informed me that on Nowruz, everyone would pile their sabzeh into their cars and drive to the mountains in an effort to find a water runoff where they could cast their greens at sea. And everyone did it even though it required navigating a traffic gridlock unlike any other.

But Nowruz isn’t all about cleaning and plant life; other rituals involve fire, money, and — stay with me — banging on pots with spoons

I grew up in New Jersey without many other Iranians, so even though my family regularly hosted a Nowruz haft-seen, we were unable to participate in some of the more social activities, which is a shame because they look like fun.

The final Tuesday before Norwuz is referred to as shab-e chahar shanbeh suri, or “Eve of Red Wednesday” (a phonetically approximate translation from Persian into English). Building public bonfires, jumping over them, and chanting “Zardi-ye man az toh, sorkhi-ye toh az man” are all part of the day’s activities. This means, approximately, “Give me your lovely red color and take back my terrible pallor!”.

The goal is to cleanse away the previous year so that you can begin the new one feeling cleansed and renewed, in keeping with Nowruz’s underlying concept of renewal.

During Nowruz, children and the elderly prosper especially well. Families will get together to pay respects at the oldest family member’s house at the start of the 13-day festival. Children will approach homes carrying cooking pots and pound on them with spoons until someone comes out and fills them with something sweet. (Like an Iranian version of Halloween, except you just demand what’s yours instead of dressing up as a vampire to grab your goodies.)

Finally, in keeping with the overall concept of a fresh start, parents and other adult family members will give children cash gifts in the shape of brand-new banknotes.

Okay, everything revolves on newness and renewal. What about the cuisine, though?

Hello, reader. Let’s discuss food.

If you are unfamiliar with Persian food, the very basics are that if you are invited to a dinner party in an Iranian home, you will probably be served a variety of grilled or braised meats and hearty stews, flavored with intensely aromatic spices (though not many of them pack much heat), and served with mountains of steamed rice. (I won’t listen to any claims that Iranian rice isn’t the best rice.) You can read more about Persian cuisine and rituals in Najmieh Batmanglij’s lovely, comprehensive cookbook Food of Life.

On Nowruz itself, though, you may anticipate a few meals that are unique to the celebration, frequently centered on greens and herbs to symbolize its themes of — say it with me now — freshness and renewal.

Most Nowruz meals will feature sabzi polow ba mahi, a herbed rice dish served with some sort of whitefish, as the main course. A kuku sabzi is a dish that involves baking eggs with a variety of herbs, including dill, cilantro, parsley, fenugreek, tarragon, and others. Kuku sabzi is “an ancient relative of the frittata,” as my mother kindly notes.

Iranians will always prepare you with more food than you can ever consume, and at the end of the dinner, you’ll still wish you could have had more.

Nowruz is primarily a celebration of the potential for new life.

The ceremonies of Nowruz are centered on community, family, and a profound regard for tradition, as is appropriate for Persian and Zoroastrian culture.

But Nowruz is more of a celebration of being able to start fresh by wiping away the sadness, muck, and dust of the past than it is about a specific day. It’s about shutting the book on one chapter and opening the next one with anticipation rather than dread. It’s about the limitless options that a blank slate offers.

The desire to begin something fresh and better is as universal as they come, which may help to explain why Nowruz has not only survived but thrived through successive generations of turmoil and wealth.